- What is appendicitis?

- What is the appendix?

- What causes appendicitis?

- Who gets appendicitis?

- What are the symptoms of appendicitis?

- How is appendicitis diagnosed?

- How is appendicitis treated?

- What are the complications and treatment of a burst appendix?

- What if the surgeon finds a normal appendix?

- Can appendicitis be treated without surgery?

- What should people do if they think they have appendicitis?

- Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

- Points to Remember

- Hope through Research

- For More Information

What is appendicitis?

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Appendicitis is the leading cause of emergency abdominal operations.

1

1Spirt MJ. Complicated intra-abdominal infections: a focus on appendicitis and diverticulitis.

What is the appendix?

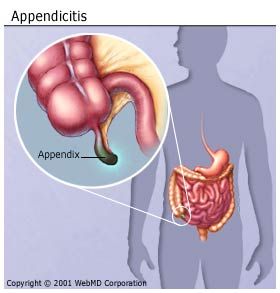

The appendix is a fingerlike pouch attached to the large intestine in

the lower right area of the abdomen, the area between the chest and

hips. The large intestine is part of the body’s gastrointestinal (GI)

tract. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined

in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus. The movement of

muscles in the GI tract, along with the release of hormones and enzymes,

helps digest food. The appendix does not appear to have a specific

function in the body, and removing it does not seem to affect a person’s

health.

The inside of the appendix is called the appendiceal lumen. Normally,

mucus created by the appendix travels through the appendiceal lumen and

empties into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water from

stool and changes it from a liquid

to a solid form.

The appendix is a fingerlike pouch attached to the large intestine in the lower right area of the abdomen.

The appendix is a fingerlike pouch attached to the large intestine in the lower right area of the abdomen.

What causes appendicitis?

An obstruction, or blockage, of the

appendiceal lumen causes appendicitis.

Mucus backs up in the appendiceal lumen,

causing bacteria that normally live inside

the appendix to multiply. As a result, the

appendix swells and becomes infected.

Sources of blockage include

- stool, parasites, or growths that clog the appendiceal lumen

- enlarged lymph tissue in the wall of the appendix, caused by infection in the

GI tract or elsewhere in the body

- inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease

and ulcerative colitis, long-lasting disorders that cause irritation and

ulcers in the GI tract

- trauma to the abdomen

An inflamed appendix will likely burst if not removed.

Who gets appendicitis?

Anyone can get appendicitis, although it is more common among people 10 to 30 years old.

1

What are the symptoms of appendicitis?

The symptoms of appendicitis are typically easy for a health care

provider to diagnose. The most common symptom of appendicitis is

abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain with appendicitis usually

- occurs suddenly, often waking a person at night

- occurs before other symptoms

- begins near the belly button and then moves lower and to the right

- is unlike any pain felt before

- gets worse in a matter of hours

- gets worse when moving around, taking deep breaths, coughing, or sneezing

Other symptoms of appendicitis may include

- loss of appetite

- nausea

- vomiting

- constipation or diarrhea

- an inability to pass gas

- a low-grade fever that follows other symptoms

- abdominal swelling

- the feeling that passing stool will relieve discomfort

Symptoms vary and can mimic the following conditions that cause abdominal pain:

- intestinal obstruction—a partial or total blockage in the intestine that prevents the flow of fluids or solids.

- IBD.

- pelvic inflammatory disease—an infection of the female reproductive organs.

- abdominal adhesions—bands of tissue that form between abdominal

tissues and organs. Normally, internal tissues and organs have slippery

surfaces that let them shift easily as the body moves. Adhesions cause

tissues and organs to

stick together.

- constipation—a condition in which a person usually has fewer than

three bowel movements in a week. The bowel movements may be painful.

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendix,

a 3 1/2-inch-long tube of tissue that extends from the large intestine.

No one is absolutely certain what the function of the appendix is. One

thing we do know: We can live without it, without apparent consequences.

Appendicitis

is a medical emergency that requires prompt surgery to remove the

appendix. Left untreated, an inflamed appendix will eventually burst, or

perforate, spilling infectious materials into the abdominal cavity.

This can lead to

peritonitis,

a serious inflammation of the abdominal cavity's lining (the

peritoneum) that can be fatal unless it is treated quickly with strong

antibiotics.

Sometimes a pus-filled abscess

(infection that is walled off from the rest of the body) forms outside

the inflamed appendix. Scar tissue then "walls off" the appendix from

the rest of the

abdomen,

preventing infection from spreading. An abscessed appendix is a less

urgent situation, but unfortunately, it can't be identified without

surgery. For this reason, all cases of appendicitis are treated as

emergencies, requiring surgery.

In the U.S., one in

15 people will get appendicitis. Although it can strike at any age,

appendicitis is rare under age 2 and most common between ages 10 and 30.

What Are the Symptoms of Appendicitis?

The classic symptoms of appendicitis include:

- Dull pain near the navel or the upper abdomen that becomes sharp as it moves to the lower right abdomen. This is usually the first sign.

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and/or vomiting soon after abdominal pain begins

- Abdominal swelling

- Fever of 99-102 degrees Fahrenheit

- Inability to pass gas

Almost half the time, other symptoms of appendicitis appear, including:

- Dull or sharp pain anywhere in the upper or lower abdomen, back, or rectum

- Painful urination

- Vomiting that precedes the abdominal pain

- Severe cramps

- Constipation or diarrhea with gas

If

you have any of the mentioned symptoms, seek medical attention

immediately since timely diagnosis and treatment is very important. Do

not eat, drink, or use any pain remedies, antacids, laxatives, or heating pads, which can cause an inflamed appendix to rupture.

How is appendicitis diagnosed?

A health care provider can diagnose most cases of appendicitis by taking a person’s medical history and performing a physical

exam.

If a person does not have the usual symptoms, health care

providers may use laboratory and imaging tests to confirm appendicitis.

These tests also may help diagnose appendicitis in people who cannot

adequately describe their symptoms, such as children or people who are

mentally

impaired.

Medical History

The health care provider will ask specific questions about

symptoms and health history. Answers to these questions will help rule

out other conditions. The health care

provider will want to know

- when the abdominal pain began

- the exact location and severity of the pain

- when other symptoms appeared

- other medical conditions, previous illnesses, and surgical procedures

- whether the person uses medications, alcohol, or illegal drugs

Physical Exam

Details about the person’s abdominal pain are key to diagnosing

appendicitis. The health care provider will assess the pain by touching

or applying pressure to specific areas of the abdomen.

Responses that may indicate appendicitis include

-

Rovsing’s sign. A health care provider

tests for Rovsing’s sign by applying hand pressure to the lower left

side of the abdomen. Pain felt on the lower right side of the abdomen

upon the release of pressure on the left side indicates the presence of

Rovsing’s sign.

-

Psoas sign. The right psoas muscle runs

over the pelvis near the appendix. Flexing this muscle will cause

abdominal pain if the appendix is inflamed. A health care provider can

check for the psoas sign by applying resistance to the right knee as the

patient tries to lift the right thigh while lying down.

-

Obturator sign. The right obturator muscle

also runs near the appendix. A health care provider tests for the

obturator sign by asking the patient to lie down with the right leg bent

at the knee. Moving the bent knee left and right requires flexing the

obturator muscle and will cause abdominal pain if the appendix is

inflamed.

-

Guarding. Guarding occurs when

a person subconsciously tenses the abdominal muscles during an exam.

Voluntary guarding occurs the moment the health care provider’s hand

touches the abdomen. Involuntary guarding occurs before the health care

provider actually makes contact and is a sign the appendix is inflamed.

- Rebound tenderness. A health care provider

tests for rebound tenderness by applying hand pressure to a person’s

lower right abdomen and then letting go. Pain felt upon the release of

the pressure indicates rebound tenderness and is a sign the appendix is

inflamed. A person may also experience rebound tenderness as pain when

the abdomen is jarred—for example, when a person bumps into something or

goes over a bump in a car.

Women of childbearing age may be asked to undergo a pelvic exam

to rule out gynecological conditions, which sometimes cause abdominal

pain similar to appendicitis.

The health care provider also may examine the rectum, which can be tender from appendicitis.

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests can help confirm the diagnosis of appendicitis or find other causes of abdominal pain.

-

Blood tests. A blood test involves drawing a

person’s blood at a health care provider’s office or a commercial

facility and sending the sample to a laboratory for analysis. Blood

tests can show signs of infection, such as a high white blood cell

count. Blood tests also may show dehydration or fluid and electrolyte

imbalances. Electrolytes are chemicals in the body fluids, including

sodium, potassium, magnesium, and chloride.

- Urinalysis. Urinalysis is testing of a urine

sample. The urine sample is collected in a special container in a health

care provider’s office, a commercial facility, or a hospital and can be

tested in the same location or sent to a laboratory for analysis.

Urinalysis is used to rule out a urinary tract infection or a kidney

stone.

- Pregnancy test. Health care providers also may order a pregnancy test for women, which can be done through a blood or urine test.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests can confirm the diagnosis of appendicitis or find other causes of abdominal pain.

- Abdominal ultrasound. Ultrasound uses a

device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off

organs to create an image of their structure. The transducer can be

moved to different angles to make it possible to examine different

organs. In abdominal ultrasound, the health care provider applies gel to

the patient’s abdomen and moves a hand-held transducer over the skin.

The gel allows the transducer to glide easily, and it improves the

transmission of the

signals. The procedure is performed in a health care provider’s office,

an outpatient center, or a hospital by a specially trained technician,

and the images are interpreted by a radiologist—a doctor who specializes

in medical imaging; anesthesia is not

needed. Abdominal ultrasound creates images of the appendix and can show

signs of inflammation, a burst appendix, a blockage in the appendiceal

lumen, and other sources of abdominal pain. Ultrasound is the first

imaging test

performed for suspected appendicitis in infants, children, young adults,

and pregnant women.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI

machines use radio waves and magnets to produce detailed pictures of the

body’s internal organs and soft tissues without using x rays. The

procedure is performed in an outpatient center or a hospital by a

specially

trained technician, and the images are interpreted by a radiologist.

Anesthesia is not needed, though children and people with a fear of

confined spaces

may receive light sedation, taken by mouth. An MRI may include the

injection of special dye, called contrast medium. With most MRI

machines,

the person lies on a table that slides into a tunnel-shaped device that

may be open ended or closed at one end; some machines are designed to

allow the person to lie in a more open space. An

MRI can show signs of inflammation, a burst appendix, a blockage in the

appendiceal lumen, and other sources of abdominal pain. An MRI used to

diagnose appendicitis and other sources of abdominal pain is a safe,

reliable alternative to a computerized tomography (CT) scan.2

- CT scan. CT scans use a combination of x rays

and computer technology to create three-dimensional (3-D) images. For a

CT scan, the person may be given a solution to drink and an injection

of contrast medium. CT scans require the person to lie on a table that

slides into

a tunnel-shaped device where the x rays are taken. The procedure

is performed in an outpatient center or a hospital by an x-ray

technician, and the images are interpreted by a radiologist; anesthesia

is not needed. Children may be given a sedative to help them

fall asleep for the test. A CT scan of the abdomen

can show signs of inflammation, such as an enlarged appendix or

an abscess—a pus-filled mass that results from the body’s attempt to

keep an

infection from spreading—and other sources of abdominal pain,

such as

a burst appendix and a blockage in the appendiceal lumen. Women

of childbearing age should have a pregnancy test before undergoing

a CT scan. The radiation used in CT scans can be harmful to a

developing fetus.

2Heverhagen J, Pfestroff K,

Heverhagen A, Klose K, Kessler K, Sitter H. Diagnostic accuracy of

magnetic resonance imaging: a prospective evaluation of patients with

suspected appendicitis (diamond).

Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012;35:617–623.

How is appendicitis treated?

Appendicitis is typically treated with surgery to remove the

appendix. The surgery is performed in a hospital; general anesthesia is

needed. If appendicitis is suspected, especially in patients who have

persistent abdominal pain and fever, or signs of a burst appendix and

infection, a health care

provider will often suggest surgery without conducting diagnostic

testing. Prompt surgery decreases the chance that the

appendix will burst.

Surgery to remove the appendix is called an appendectomy. A surgeon performs the surgery using one of the following methods:

- Laparotomy. Laparotomy removes the

appendix through a single incision in the lower right area of the abdomen.

- Laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic surgery uses several smaller incisions

and special surgical tools fed through the incisions to remove the appendix. Laparoscopic surgery leads to fewer

complications, such as hospital-related infections, and has a shorter recovery

time.

With adequate care, most people recover from appendicitis and do

not need to make changes to diet, exercise, or lifestyle. Surgeons

recommend limiting physical activity for the first 10 to 14 days after a

laparotomy and for the first 3 to 5 days after laparoscopic surgery.

What are the complications and treatment of a burst appendix?

A burst appendix spreads infection throughout the abdomen—a

potentially dangerous condition called peritonitis. A person with

peritonitis may be extremely ill and have nausea, vomiting, fever, and

severe abdominal tenderness. This condition requires immediate surgery

through laparotomy to clean the abdominal cavity and remove the

appendix. Without prompt treatment, peritonitis can cause death.

Sometimes an abscess forms around a burst appendix—called an

appendiceal abscess. A surgeon may drain the pus from the abscess during

surgery or, more commonly, before surgery. To drain an abscess, a tube

is placed in the abscess through the abdominal wall. The drainage tube

is left in place for about 2 weeks while antibiotics are given to treat

infection. Six to 8 weeks later, when infection and inflammation are

under control, surgeons operate to remove what remains of the burst

appendix.

What if the surgeon finds a normal appendix?

Occasionally, a surgeon finds a normal

appendix. In this case, many surgeons will

remove it to eliminate the future possibility

of appendicitis. Occasionally, surgeons

find a different problem, which may also be

corrected during surgery.

Can appendicitis be treated without surgery?

Nonsurgical treatment may be used if surgery is not available, a

person is not well enough to undergo surgery, or the diagnosis is

unclear. Nonsurgical treatment includes antibiotics to treat infection.

What should people do if they think they have appendicitis?

Appendicitis is a medical emergency that requires immediate

care. People who think they have appendicitis should see a health care

provider or go to the emergency room right away. Swift diagnosis and

treatment reduce the chances the appendix will burst and improve

recovery time.

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

Researchers have not found that eating,

diet, and nutrition play a role in causing or

preventing appendicitis. If a health care

provider prescribes nonsurgical treatment for

a person with appendicitis, the person will be

asked to follow a liquid or soft diet until the

infection subsides. A soft diet is low in fiber

and is easily digested in the GI tract. A soft

diet includes foods such as milk, fruit juices,

eggs, puddings, strained soups, rice, ground

meats, fish, and mashed, boiled, or baked

potatoes. People can talk with their health

care provider to discuss dietary changes.

Points to Remember

- Appendicitis is inflammation of the

appendix.

- The appendix is a fingerlike pouch

attached to the large intestine and

located in the lower right area of the

abdomen. The inside of the appendix is

called the appendiceal lumen.

- An obstruction, or blockage, of the appendiceal lumen causes appendicitis.

- The most common symptom of

appendicitis is abdominal pain. Other

symptoms of appendicitis may include

loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting,

constipation, diarrhea, an inability to

pass gas, a low-grade fever, abdominal

swelling, and the feeling that passing

stool will relieve discomfort

- A health care provider can diagnose

most cases of appendicitis by taking a

person’s medical history and performing

a physical exam. If a person does not

have the usual symptoms, health care

providers may use laboratory and

imaging tests to confirm appendicitis.

- Appendicitis is typically treated with surgery to remove the appendix.

- Nonsurgical treatment may be used

if surgery is not available, a person is

not well enough to undergo surgery, or

the diagnosis is unclear. Nonsurgical

treatment includes antibiotics to treat

infection.

- Appendicitis is a medical emergency that requires immediate care.

- If a health care provider prescribes nonsurgical treatment

for a person with appendicitis, the person will be asked to follow a

liquid or soft diet until the infection subsides.

Hope through Research

The National Institute of Diabetes and

Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)

and other components of the National

Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and

support basic and clinical research into many

digestive disorders, including appendicitis.

Clinical trials are research studies involving

people. Clinical trials look at safe and

effective new ways to prevent, detect, or

treat disease. Researchers also use clinical

trials to look at other aspects of care, such

as improving the quality of life for people

with chronic illnesses. To learn more about

clinical trials, why they matter, and how to

participate, visit the NIH Clinical Research

Trials and You website at

www.nih.gov/health/

clinicaltrials. For information about current

studies, visit

www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

For More Information

American Academy of Family Physicians

P.O. Box 11210

Shawnee Mission, KS 66207–1210

Phone: 1–800–274–2237 or 913–906–6000

Email:

contactcenter@aafp.org

Internet:

www.aafp.org American College of Surgeons

American College of Surgeons

633 North Saint Clair Street

Chicago, IL 60611–3211

Phone: 1–800–621–4111 or 312–202–5000

Fax: 312–202–5001

Email:

postmaster@facs.org

Internet:

www.facs.org American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons

85 West Algonquin Road, Suite 550

Arlington Heights, IL 60005

Phone: 847–290–9184

Fax: 847–290–9203

Email:

ascrs@fascrs.org

Internet:

www.fascrs.org

how to sell a diamond